So, Wallsend eh? Growing up, I always thought it was a funny name, up there with the likes of Pity Me and Tantobie, to cite just two brilliantly-named north eastern locations. But I’ve just been for a visit and found out Wallsend’s even sillier Roman name – Segedunum!

Segedunum is the Roman fort at one end of Hadrian’s Wall, that amazing national treasure built across the Northumbrian and Cumbrian countryside to keep out those scary Picts. The settlement is not qute as large as the incredible Vindolanda site further along the wall, but its definitely worth a visit.

Having said that, though – if you ever wonder why historians get excited about discovering a series of small walls, then you might be even more curious about us showing excitement when some of the missing walls have been filled in with even smaller walls of contemporary cobbles. Not even the real archaeological deal, just something indicating the original lie of the land.

But it is interesting – a real eye opener showing the arrangement of life in a Roman fort. The cavalry barracks with their arrangement of rooms for officers and horses – hearth at the front denoting a room for three cavalry men, and the room at the back with a big pit for draining away the urine of the three cavalrymen’s horses. The hospital latrine with it original arrangement of drains and the channel from the water tank showing the hygiene logistics of the camp. The grandeur of the commanding officer’s house built to reflect the rich Roman villas of the Mediterranean – including the shaded courtyard to protect them from the Northumbrian sun!

At the far end of the site is a reconstruction of the bath house, sadly closed to the public due to a large whole in the roof, rendering it unfit and unsound for visitors. Luckily for us, there is a reconstruction of the bathhouse floor plan further along Hadrian’s Cycleway – about 200 metres from the main site. The verge of the Cycleway and parts of the site itself were in full bloom with wild flowers planted courtesy of the remainder of a half million pound grant awarded by ex-chancellor George Osborne – surely one of the very few gestures by a Tory government for the benefit of the north east, even the attendant at the museum, rolled her eyes in confusion at the thought!

It was a grey day when we visited, but the site was in glorious colour thanks to the wild flowers filling the verge of the cycle path – thanks in part to Mr Osborne’s £500,000 grant. The small Roman garden by the now-defunct bathhouse was also quite lovely, with places to picnic if the rain held off.

Segedunum – Seg (rhyming with egg)-u-due-num, if you’re asking (‘Seggy’ for short, according to the attendant) – consists of the restored section between the roadside and the cycleway, the new bathhouse site and an informative purpose-built museum with viewing gallery.

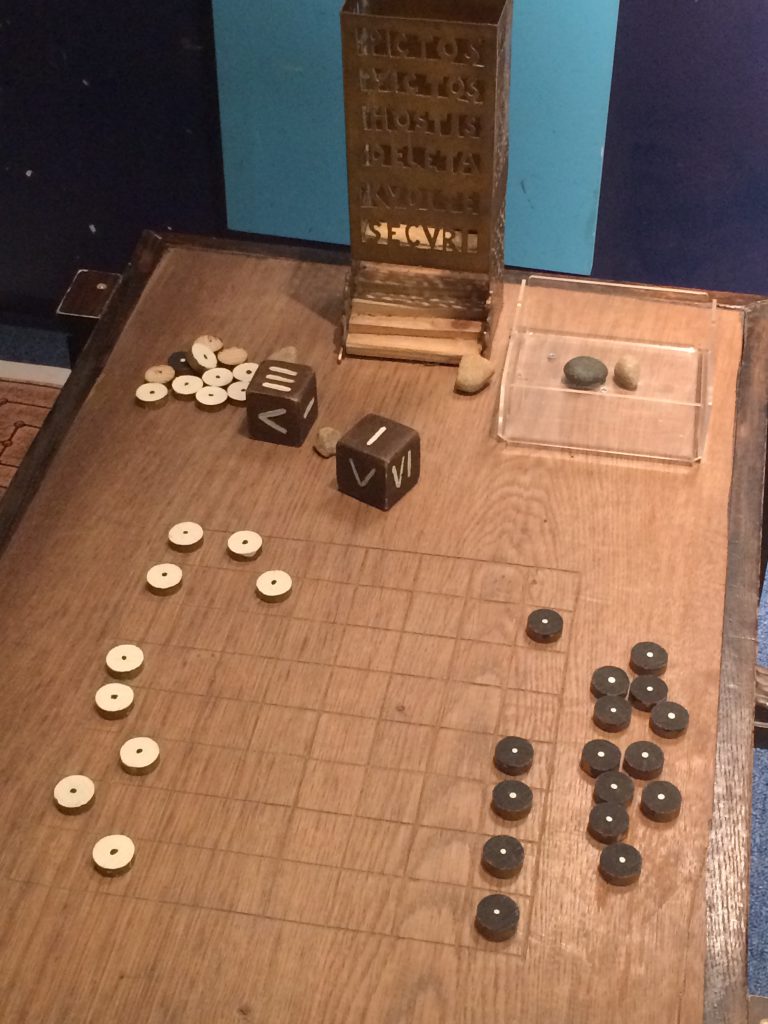

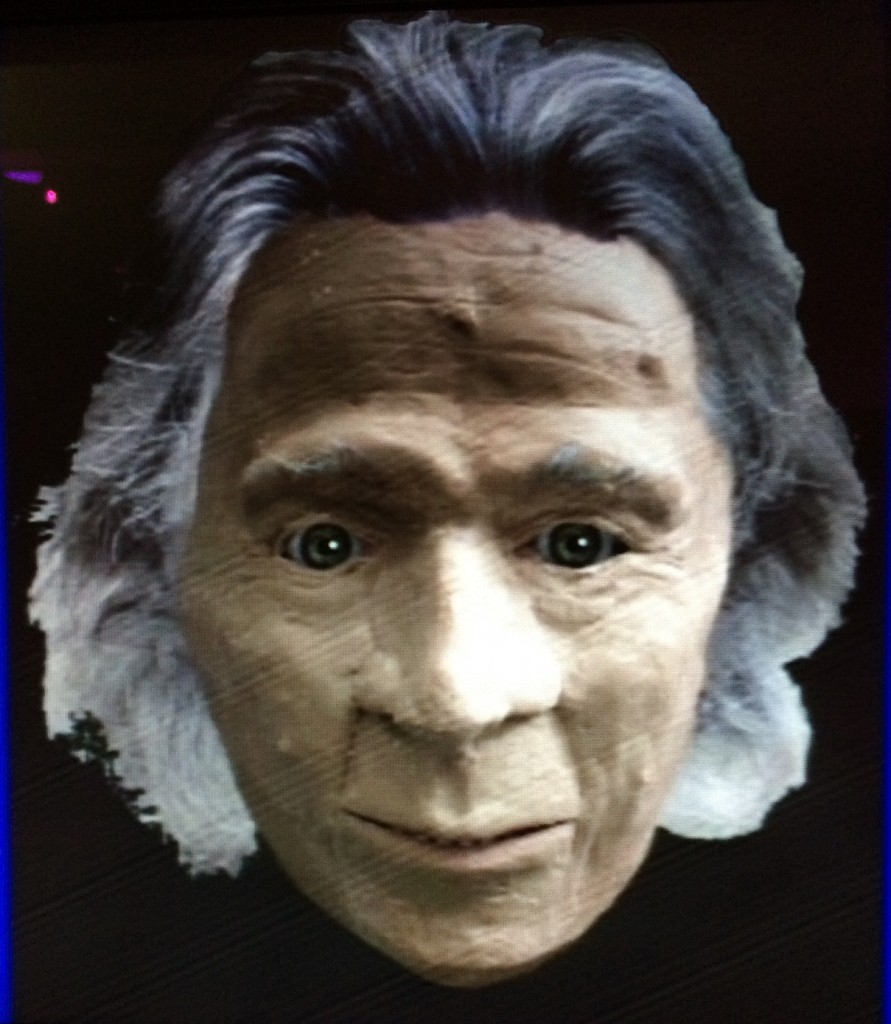

I must admit that Mr Jenkins and I thought the viewing gallery was an airport control tower, but the elevated section of the museum helps you to view the whole site with the help of an animated timeline, taking you from the Roman invasion of Britain, through the abandonment and decay of the camp, it’s return to nature, and then, in the Victorian industrial era, a building flurry of terraced housing, quickly demolished as time flies by to the excavation of the site and renovation of the original Roman fort. The top of the tower, on level 9, is served by a lift, so you don’t have to climb all the stairs. Strangely, levels 8 to 4 don’t exist, so it’s straight down to the cafe on level 3 and the galleries on levels 1 and 2. The staff are friendly and there were a bunch of tame Romans around adding colour to the story of the fort. The Romans, in full regalia, were hanging around the car park and mingling with visitors on level 1, where items excavated from the grounds were displayed with interactive displays, and films explaining the social structure of the Roman and indiginous inhabitants.

It’s an interesting place, not over-packed with info, making it accessible for those tempted in for a quick idea of the place, or children with a shorter attention span. The in-depth details are imparted from an engaging film showing characters from the heyday of the fort, and from their modern-day counterparts with their brightly coloured armour and weapons.

The museum employees pointed us up to the viewing gallery first, but recommended a trip to the main gallery to chat with the Romans before they knock of at 3pm. The tea room would be closing early too, so get yourself up there if you need a cup of tea… Duly instructed we were up in the friendly, if almost empty, tea room by 3.30pm overlooking the site of the fort and the car park, just in time to watch the Romans pack their armour into crates and lug them into the boot of their cars.

Back down to level 2 and a bit more information about the colliery and shipbuilding. Not quite as exhaustive as the Roman exhibits, but interesting none-the-less. However, it is the museum’s Roman credentials that make this place, and the exhibits work hard at emphasising the day-to-day life of the fort and its interaction with the existing community. It made me wonder why I always spurned the offer of a trip to Housesteads when I was younger. Housesteads, that other popular Roman site on Hadrian’s Wall and popular destination for boring Latin teachers….. Perhaps I was just waiting for technology to catch up to make the visit a tad more interesting.

Segedunum is open to public from the 1 April to the 30 September, daily from 10am-5pm. Entrance fees are £5.95 for addults, £3.95 for concessions and children under 16 go free.